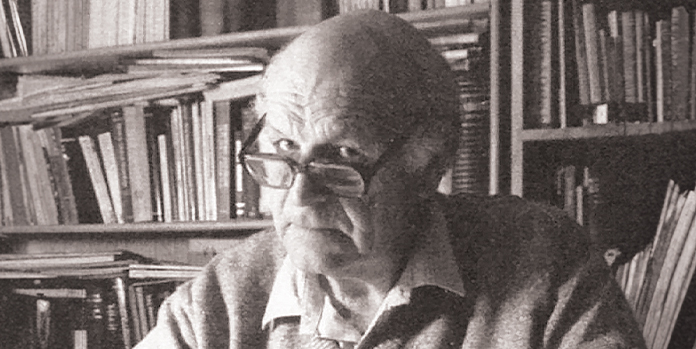

John Birrell ISO OAM (OM 1941)

As Melbourne’s Police Surgeon, Dr John Birrell ISO OAM (OM 1941) saw the effects of drink driving, speeding, and lack of seatbelts first-hand. His experiences over 20 years in the role transformed him into one of Victoria’s most important road safety pioneers, alongside fellow Old Melburnian, Morris House member and road safety advocate Gordon Trinca AO OBE (OM 1939).

Both persevered, even as their work made them unpopular with politicians and industry leaders.

Taking on the alcohol industry

Following his discharge from military service in 1946, John completed his medical degree and began working in hospital casualty rooms.

In 1956, he was appointed to the role of Assistant Coroner’s Pathologist in 1956, John was tasked with drawing blood samples from drivers involved in accidents and quickly saw the reality of road trauma.

Never one for shying away from speaking his mind, within two weeks of his promotion to the role of Police Surgeon in 1957 – a position he would hold for the next 20 years - John had called a press conference to announce that alcohol was a significant contributor to fatalities on the road.

“If a compulsory blood test were given to everyone associated with a serious accident, this state would be rocked by the results,” John told the media. His estimate that around 60% of accidents involved alcohol consumption contradicted members of the liquor industry, who insisted the figure was closer to 5%.

“Dad got into trouble with the Hotels Association, the RSL, Carlton United Breweries—they tried to shut him down,” says son Mike Birrell. “He also fought plenty of backlash from the government including the then Premier Henry Bolte and other senior politicians, but he didn’t stop for anything.”

But, with a brilliant mind, an undeniable ‘presence’ and a fierce determination, he was hard to ignore.

Being on the scene led to further resolve

On call 24 hours a day, John was regularly called to traffic accidents and his exposure to the carnage on Melbourne roads further aroused his anger. He was horrified at the increasing number and severity of fatalities and injuries he witnessed.

John also recognised that, while people don’t always die in traffic accidents, the terrible damage that came from passengers being catapulted through the windscreen and the chest and brain injuries that drivers often suffered could have life changing impact. He was just as determined to stop these tragedies occurring.

Undeniable evidence creates change

With powerful interests set against legislative change, John knew he would have to work hard to win over key players. He published his own research on drink driving, speeding and seatbelt use, worked closely with the media to disseminate his findings, and delivered lectures—complete with shocking photos from crash sites—to convince the people he needed on his side.

He served on numerous national and international committees, presented at significant forums and conferences and was regularly in the news presenting his views and findings.

John Birrell was tireless and unrelenting.

In 1959, he collaborated with Graham Perkin a journalist from The Age who launched the renowned 'Blood on Bitumen' campaign highlighting the dangers of drink driving and promoting the need for seat belts for cars, crash helmets for motor cyclists and crash bars for motorcycles.

Following the publication of these articles, many remained sceptical of John’s assertions, or at least, wanted the publicity to cease. With mounting pressure from influential figures urging the government to silence John, Lindsay Thompson then Victorian Assistant Chief Secretary and later Premier, was tasked with conducting an investigation.

“One of the smartest things my father did was to take Lindsay Thompson out on Friday and Saturday nights to see these crashes up close. Lindsay had been a strong voice against the changes my father was seeking. After his experiences on those nights Lindsay went back to the government and said: ‘We do have a problem, and it’s not John Birrell,’” says Mike.

Largely due to John's campaigning, a Breath Tests Act was introduced in Victoria in 1961 - the first state to do so. It brought about mandatory breathalyser testing for those drivers who were suspected of being drunk. It also meant police could get blood alcohol readings quickly and easily – and, notably, before an accident had occurred - thereby both increasing their ability to remove drunk drivers from the road before they caused harm, and improving the statistical information available about the level of drink driving on our roads.

Legislation limiting driver’s blood alcohol limit to 0.05 came about five years later. Random breath testing was legislated in 1976 in Victoria.

Then, in 1970, legislation for the mandatory wearing of seat belts was introduced in Victoria – the first jurisdiction in the world to do this.

John also “put motorbike helmets on motorbike riders, shifted electricity poles back from the road, changed car design [for example, removing knobs from the dashboard which could cause significant harm in an accident]” according to Mike. “He was always at the vanguard of these type of issues.”

A focus on other societal issues

While John was unswervingly devoted to the road safety cause, he also found time to support the work of his brother, Dr Bob Birrell OAM (OM 1950), whose research and advocacy against child abuse led to vital changes across our hospital system.

In the 1960s they co-authored two seminal papers which documented the number of children being admitted to the Royal Children’s Hospital with shocking, inexplicable injuries. They were faced with complacency and disbelief. However, today, many of the changes they recommended in the papers – and campaigned for – have since come into fruition, ultimately making the world safer for countless children.

“He was one of the greatest medical pioneers we’ve had in this country,” Mike adds. “It’s because of his work that people now have the luxury of focusing on the damage done to their car in a road accident, rather than ending up in hospital [or worse].”

He was awarded Companion of the Imperial Service Order in 1978, and a Medal of the Order of Australia in 1997 in recognition of his service to medicine and the community.

The University of Melbourne recognises his achievements through the JHW Birrell Scholarship which is awarded to a student undertaking research in a field relevant to road safety.

On his death in 2003, The Age estimated that John’s work may have saved 30,000 lives. Today, it is certainly many, many more.